On a spring day in 1953 on Illian Meadow across the Kamenka River and beneath the walls of the Suzdahl Kremlin, Danton Larionov, son of the NKVD executioner and a bully, spies the stranger, fourteen-year-old Ekaterina Soroka, daughter of the dancer and a storyteller. He makes ready to rape her. She disarms him.

Kiev, Vladimir, Suzdal and Moscow––These four city names symbolize the most important stages of Russian medieval history. Suzdal has become a character in my next novel (working title The Executioner’s Son). Suzdal’s history intertwines with Vladimir’s, so much so that in Western history books, their names are hyphenated, i.e. Vladimir-Suzdal. English-language materials describing the region tend to be tourist-brochure level of detail, so I am translating Russian-language monographs, a labor-intensive task, truth be told. I’ve posted the translations here and will update it periodically. It is a work in progress, which I work on when I can do no more creative work.

Suzdal is located in a region of rich black earth laid down by the Klyazma river and extending along the right bank of the river, Nerl, with passes through and joins the Kamenka River in Suzdal. The left bank of the Nerl, a region of poor and thin soils, contains numerous stone grave markers of a pre-historic peoples––hunters, fishers, gatherers––which yield bones, old axes, and other tools. The Nerl joins the Kamenka River in Suzdahl. The road to Kiev passed through Vladimir and onto Suzdahl.

Golden Gate, Vladimir, Russia

Vladimir, Russian Federation

Ancient Vladimir occupied a plateau riven with deep ravines on the left bank[i] of the Klyazma River. The original site was located about fifty meters above the course of the river, naturally well-defended. The Klyazma river in those days was a mighty, heavy-flowing river, the town established at a location which allowed communication and trade with Eastern Europe via the Volga River. Even up to the 12th century the city gates opening out onto the Klyazma were called the Volga gates, not the Klyazma gates.

Archeological excavations indicate Slavic settlers moved into the forests of North East Russia in the 9th century, probably to escape nomad raids they suffered clustered along the great rivers systems––the Volga, Dnieper, Dniester––flowing across the Great Steppe of Central Asia which they shared with fierce nomadic tribes.

The old manuscripts identified the whole area as ’Syzhdal’, but designated not only the trade and handicraft area along the Kamenka River, but the whole right bank of the River Nerl, It was connected via trade routes, excavations showing connections via the Volga, Oka, Klyazma and Nerl Rivers. The Kamenka River was not navigable upstream beyond Suzdah. Coinage from Samarkand, Bukhara, Germany is found in sarcophaguses in the region.

In the 11th century the territory witnessed a series of bloody feudal wars for control of the NW territory of the Kievian Ruc’.

The imposition of feudalism in the beginning of the 11th century resulted in uprisings, the suppression of which caused widespread starvation. In 1096 the forces of Mistislav of Novgorod, son of Vladimir Monomakn, burned Suzdal. Only the monastery complex of the Pechera remained standing.

In 1107 The Bulgars attacked Suzdal. The Rostov Chronicles noted the “The Bulgars surrounded the fortress, causing great losses among the defenders and killed many Christians.”

Until the early 13th century these dynastic wars and raids and uprising punctuated the history of the region, bloody enough, though no more (nor less) ravaged than any other piece of Russian urban real estate. Medieval dynastic wars similarly ravaged the populations of England, Poland, Germany, Spain, Scandinavia, France, the Low Countries.

However:

The Mongols brought their brand of steppe warfare to Kievian Ruc’ in the year 1238. The northern forests didn’t hide them. Batu Khan, son of Genghis, found them, slaughtered them and enslaved the survivors. This is the genetic memory of Slavs.

The British military historian John Keegan posits in The History of War that the history of warfare until most recently was the history or warfare between the herder and agriculturalist. When herds diminished or disappeared, the nomad went hunting next where the food was stored––the settlement. Skirmishes, battles and wars ensued.

The conflict between the herder and the farmer was the original conflict. One interpretation of the Cain and Abel story is that it reflects the very ancient tension between the different values and ways of life of wandering herders, represented by Abel, and settled farmers, represented by Cain.

The herder practiced warrior skills; once the flock was at grass or water, he had little else to do but master the skills required to defend the flock against wolf, bear and cat. The weapon against the lion was equally effective against the ploughman. David, the shepherd, with the sling slew Goliath, wielder of heavy axe.

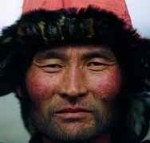

Mongol Herder

Sitting Bull, Sioux War Chief

The Mongols, nomadic herders of the Altai region share their genotype with the Amerindian; In Robert O. Kaplan’s Imperial Grunts: The American Military On The Ground, quotes US Army advisors to the Army of Mongolia, foreign area officers who deploy from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas (from which General George C. Custer led troopers of US 7th Calvary out to suppress the Sioux and Cheyenne). They observe Sioux chief Sitting Bull’s twin brothers a dozen times a day on the streets of Ulan Bator; they advise Crazy Horse’s cousins how do defend against Han Chinese border incursions.

[i] That bank of a stream or river on the left (right) of the observer when facing in the direction of flow or downstream.