Victorious fathers, American and Soviet, returned from far-flung fronts, nightmares lingering in their memories and in the collective memory of their nations. Deception, deceit, surprise attack, Pearl Harbor or Barbarossa, are burned in memory. Stories told, films made, posters painted and songs sung shaped lessons learned, enemies identified, future imagined.

In my hometown, two young men, sons of upright families, had fought. One fell the other with a baseball bat. He did not die, but regained consciousness some weeks later. He was not the same, slow to form a sentence, his memory of that night confused. Thus had our fathers returned, as if concussed, to frame the future.

In 1947, Soviet security services identified the United States as the ‘main enemy,’ replacing Great Britain. Sons and daughters grew of age with stories, fears and hopes, fragmented in telling and memory.

The Cold War was joined. The sons would fight. The Long War series is about sons and daughters; Richard Belisle and M.J. Charbonneau, Danton Larionov and Ekaterina Soroka, children of their nations’ greatest generation, born half-worlds apart, come of age each in their small-town Eden, bathed in stories, tales and memory. Each is cast out to stalk one other on the front lines in the war for control of the imagination. They cross paths and cross swords, trust and double-cross, become fast friends and bitter enemies, remain faithful and deceitful, striving to be moral in an immoral world.

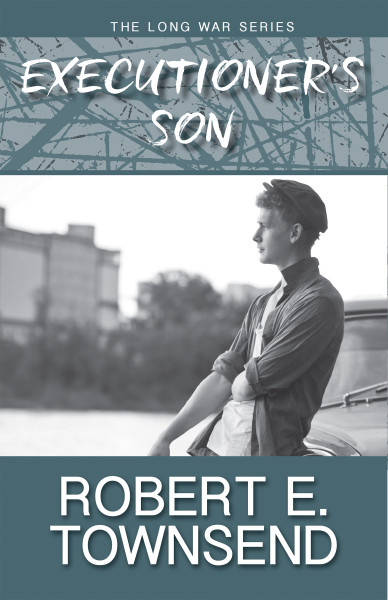

The Executioner’s Son is the third volume in Townsend’s five-book series, The Long War, set against the background of ruse and stratagem between the Soviet Union and the United States. The novel opens in 1953 in Suzdal, Russia’s medieval religious center and ancient capital, now a GULAG. Its former monasteries, nunneries, and fortresses are NKVD prisons. Screams punctuate the night. The spring thaw, the Rasputitsa, extrudes the murdered from the earth.

On a spring day, the youthful Danton Larionov, son of NKVD officer, Captain Volk Larionov, encounters thirteen-year-old Ekaterina Soroka, the Ukrainian, on the meadow beneath the Suzdal Kremlin. He forces himself upon her, but she pauses him with a fairy tale. Through the summer as Stalin’s death convulses the Soviet Union, she tells him Russian tales, holding him at bay. In the fall, she disappears. Danton, stunned, had fallen in love.

A decade later, Danton, rejecting his father’s trade and connections, now a Soviet Army engineer, receives a coveted assignment to the Kuibyshev School of Combat Engineering, Moscow. The Director of Deception Studies is one Colonel Alexander Soroka, ‘the sorcerer’, whose WWII exploits in the arts of misdirection are legendary.

Could the storyteller, Ekaterina––the name Soroka is as common in the western Soviet Union as Williams or Smith is in Middle America––have had some connection with the magician? The Russian and Soviet states struggled against tribal loyalty since Ivan the Terrible’s Oprichnina; Danton had switched tribes, changed loyalty from the security services to the Army. Danton Larionov becomes the master’s student to ply this art against the ‘main enemy.’

It is she. His rekindled love cripples him. He has fallen in love with the daughter of a powerful Communist with influence at the highest levels of the Soviet State. Ekaterina belongs to a powerful Soviet family, but yearns for the kingdom beyond the seventh sea. Her imagination lies in Western Europe, France or England, or hope beyond hope, America.

Danton the bully seeks the love of the Ekaterina the storyteller. conflicted in his loyalties, must tread with care amidst Soviet tribes–the party, the army, the security organs. He is exiled to a distant land, where, on a flooded Laotian river crossing, the American sniper, SP-4 Richard Belisle, frames the Danton within the crosshairs of a talisman hunting scope.

Early reviews of The Executioner’s Son

Townsend shows a deep and sensitive knowledge of the immense suffering the millions of deaths in the war the millions who died in the gulags and how it was etched into the souls of the people. His cultural and linguistic insights, blended with historical and military history, are seen through Danton and Ekaterina. James R.C. Cook, Professor of Linguistics, Towson State, Md.

Townsend’s depiction of Soviet life is as I remember it. LtCol Bill Burhans, USAF (ret)