Jon Einarsson

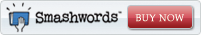

Jon Einarsson crossed the parking lot to the The VFW Post in Iron Mountain, Michigan, a single-story building sided with local material––varnished and rounded remnant ends of sawn white pine logs––and in the local style––an asphalt-shingled single-story cabin. He stepped through the storm door, opened the interior hollow core door and looked around, saw the twenty or so men sitting in chairs and around tables, and nodded to this one or another seated before his noon bump and beer, and moved to a steel folding chair against the back wall. It was a big crowd these days. WWII veterans and the few Korean War vets were getting on in years, fewer and fewer around. Jon was the single Vietnam veteran in the room; his generation inclined toward the Vietnam Veterans, tended towards Harley’s, and drugs.

Ingmar Heikkinen, State Farm insurance agent and post commander, was speaking with the active duty Army Colonel. Jon gazed across the smoky room. There he stood, Colonel Belisle. Who would have thought? It had been two decades ago, Berlin 1972…73. Some close and sensitive observer––wife, sister, mother––would have seen the flicker of emotion cross Einarssen’s face like an imperceptible movement of air ripple the waters of a Lake Superior cove. He bent at the waist as if his abdominal muscles had clenched and the still Lake Superior cove became ice-filled and gray, the sound mournful, like ice grinding on ice.

Jana Lee Nielssen, the blue-eyed Associated Press stringer––tough, ambitious, and cunning Jana with waist-length auburn hair, born of the American plains, had played this stolid Norwegian of the dark north woods. He inhaled to no relief, the oxygen seeming to glow the banked embers that were his viscera. She had been the one. She had taught him to love. He would no longer be an asshole to women. He was a catch that would honor her with his marriage proposal.

She refused him. Dazed. Stunned. Knocked unconscious, as on the football field. Had it been winter when she left? “You want a beer, Jon…” The waitress stood before him, “before the presentation.”

“Excuse me? No, no, that’s okay. Is there coffee up there by the bar?”

“I can get you some. You take sugar, right?”

“I’ll get it myself. You don’t have to put yourself out.”

“Just sit, Jon. I remember now. You just take milk.” Ah. Her name came back. Joannie. They had graduated high school together. He had been too shy to date her much less bed her. She had stayed. He had left. Heikkennen stood at the podium tapping his coffee cup against wood. “We are honored to have Colonel Richard Belisle, most remembered for his 1961 pitching debut pitching for Upson, Wisconsin where we tagged him for four home runs…” The audience chuckled. “Eichelkraut, you put one of his into Lake Superior, if I remember right.”

Eichelkraut, built like a bulldozer, demurred. It had been a check swing. The ball didn’t make it but halfway to the lake. The colonel smiled, raised his hands, palms forward. “Superior is what…about 80 miles north?” They remembered the kid, the local boy who had made good. The colonel, tall, broad-shouldered, medal-bedecked, stepped to the podium.

#

“Einarsson? ” Colonel Belisle stood before him, hand extended. “That you?”

“It’s been awhile, Sir.”

“You from around here?”

“Upper Peninsula born and raised…high school in Sault St. Marie, American side.”

“I hadn’t known you were a fellow northwoodsman. But truth be told, I’m from the more civilized side…” He smiled, the tone comforting and self-deprecating, the patter of the landsman. “…northern Wisconsin.”

“We come from long lines of cannon fodder, sir.”

“I hear you left the Air Force.” Jon nodded, surprised somewhat that the remote and austere colonel would have given such a piece of news any notice. “You come out of the incident all right?”

“I never got a chance to thank you, sir. The submission was downgraded to Legion of Merit, but it saved me.”

“I wouldn’t have written you up had you not deserved it. It was a fine piece of work.”

“It appeared at the right time. I was sitting on an Article 15…next step courts-martial. I have to admit it was a bad time. You put your career on the line, sir.”

“You call them like you see them.” Belisle shook his head in the negative to look Einarsson square in the eyes. “You put your ass on the line, soldier.”

“Airman, sir.”

Colonel Belisle swept his arm to encompass the room and men in checked shirts, suspenders, Sorel boots, chatting about weather, pulp wood and small town affairs. “I promote you to ‘soldier.'”

Jon averted his face, followed the gesture that the colonel not see his eyes mist. He had considered accepting the non-judicial punishment. He had considered shooting himself. he had visited the battlefield at Verdun while awaiting the decision of the Chief of Staff Intelligence Europe . At that moment he would have followed Belilse over the top of one of those trenches.

The colonel noticing Einarsson’s discomfort, said, “Speaking of nothing, I hear that that reporter…What was her name, that Swedish…Norwegian girl, Gustafson? Hanson? No, Nielssen…is in Europe with CNN or the Washington Post. You two seemed to have something going then.”

“Yes…”Einarsson swallowed the ‘sir.’ He didn’t want to appear a toady. “You noticed?”

“Mrs. Belisle noticed. Marie-Jeanne is a jujitsu master in affairs of the heart. If ever I had to break a hard-nosed mass murderer enemy agent within the hour, I’d bring in Marie-Jeanne…give her 15 minutes.”

“I’d like to buy you lunch, sir, if you have time. The Curve-Inn has the greasiest pasties and home-fries north of Biloxi, but they’re hot.”

The colonel seemed to consider. “How’s its coffee?”

“Look down through from the top, you can see the bottom.”

Belisle checked his watch. “I’d like that. I need to be at the VA hospital by 1500.

“You okay, sir?”

” My father’s there…not doing well.”

“I’m sorry to hear that, sir.”

“You go ahead, I’ll be there shortly.”

*

Lott Belisle

“God, let me die,” Lott Belisle cried out, the agonized plea trailing off into a moan. He lay naked, the sheets tossed off, in unendurable pain. “Let me die.” He thrashed on the single bed, an air bubble in the catheter tube advancing an inch, his anus extruding excrement.

The Iron Mountain, Michigan, Veteran’s Administration hospital room was clean, its walls pale green, the bed military functional, the stainless steel stand holding the drip new…newish.

Colonel Richard Belisle, erect in the steel chair, watched his father, a once-hard man unmasked, the dark blemishes on his chest like the unbleeding wounds of grenade shards. He felt as if he were perched at the transom, conscious only of a ringing in his ears as if a friendly round had fallen short.

His mother, Berta, eyes hypoxia-dulled and lungs ravaged with emphysema, an oxygen tube threaded beneath her nose, sat at the head of the bed.

Marie-Jeanne caressed Lott’s temple, passed her hand over his stubbled jaw, and the dying man calmed, his face moving into the touch, his body exuding gratitude. She glanced at her husband, and her expression became apprehensive. Her father-in-law, as if sensing her absence, began to hoot terror-filled animal cries, wretching her attention back to the death bed, from her husband to her father-in-law, in an emotional triage.

The duty nurse entered, efficient, kind, brisk, and checked the drip, eye-balled the saline solution level, changed the urine bag, and wiped away the excrement. She and Marie Jeanne spoke in murmurs, then the nurse turned to Berta. “Can I get you something, Mrs. Belisle, water, coffee?”

Berta looked up, slow to comprehend, and the nurse was patient as if she did not have twenty others to attend. Berta shook her head once, no, and returned her gaze to the bed, Lott’s moaning monotonous, inarticulate, as if muttering a rosary. Marie Jeanne cocked her head as if listening to a piano tuner adjusting a troublesome string, gazing through the window and across the forest crowns.

Richard looked down upon a manikin resembling himself, which occupied the steel chair, the scene a still life, like a painting hanging in the Berlin-Dahlem Museum. He shook his head as if the movement might cause the amber to melt, break, shatter, something.

The gesture succeeded. The nurse had laid her fingers to the dying man’s throat. Marie-Jeanne looked into the woman’s eyes. The liquefaction of amber paused. Richard squinted and the nurse removed her hand from Lott’s throat, bent her knee to the old woman and said, “Berta, Lott has died.”

#

Burial

Low clouds dropped heavy snow through the still air onto the chapel’s snow-laden roof and onto the cemetery stones. White pines bounded the forest clearing on the north and west. A boulder-strewn river course, upon which an otter had grooved a track between ice crevices, was the churchyard’s west boundary. A green John Deer backhoe stood next to the chapel, a discordant splash of summer green upon a winter tableau––the white of the chapel and the snow, the black of the forest and heavy coats of the mourners. Pick-up and logging trucks, cars, and the hearse parked along the county highway, beyond which lay a corn-stubbled field and a hardwood forest.

Low clouds dropped heavy snow through the still air onto the chapel’s snow-laden roof and onto the cemetery stones. White pines bounded the forest clearing on the north and west. A boulder-strewn river course, upon which an otter had grooved a track between ice crevices, was the churchyard’s west boundary. A green John Deer backhoe stood next to the chapel, a discordant splash of summer green upon a winter tableau––the white of the chapel and the snow, the black of the forest and heavy coats of the mourners. Pick-up and logging trucks, cars, and the hearse parked along the county highway, beyond which lay a corn-stubbled field and a hardwood forest.

Father Vukelich stood next to seated Berta Belisle and Zoran Karaklajic beneath the funeral tent at the grave’s head, the excavated dirt hidden beneath outdoor carpet. Beyond, was the VFW honor guard, two tall, gaunt identical twins, Kurt and Kyle Lange, the pudgy and short Dieter Weatherhogg between.

The soft fall of snow brought music, a fragment of piano music in a minor key, to her inner ear. Marie-Jeanne searched her repertoire––Chopin’s Nocturne in C Sharp minor? She listened to an additional two bars. No, it was Schubert, his dismal and foreboding Erlkonig, a Goethe poem set to music. From across the corn field, she caught a flicker of blaze orange. It was the first day of deer hunting season.

Father Vukelich, crippled by arthritis and leaning on a cane, adjusted his douillette, stepped from beneath the tent, opened his Bible, examined with distaste the falling snow and, taking off his spectacles, closed it. He had buried sufficient number of peasants to know the Rite of Committal by heart. A few words here and there out of order would not divert this dead pagan’s soul from its divine plan, which was an eternity in hell. The priest gave Marie-Jeanne Belisle nee Charbonneau a sour look.

Fuck him. Marie-Jeanne straightened to her full 5’4″. She was elegantly dressed––tall boots, long black skirt, hooded woolen cape––save for her husband’s old leather mittens, ‘choppers’ in the local parlance, lighter fluid hand warmers inside. Her fingers were always cold, her Ricky’s cross to bear if he wished to sleep with her––’Ta choix, mon cher mari. Where…back, stomach, armpits… shall I warm them?’ She placed her mittened hand upon her husband’s arm.

“Our brother, Lott Belisle, has gone to his rest in the peace of Christ. May the Lord now welcome him to the table of God’s children in heaven. With faith and hope in eternal life…”

Marie-Jeanne had brow-beaten the priest into reading the liturgy.

‘Lott’s not Catholic. The bastard’s not anything,’ he said.

‘He accepted God’s grace at the moment of death,’ she replied, then purchased the indulgence, Father Vukelic’s airline ticket to pilgrimage to Medjugorje, Yugoslavia. A disciple of the Croatian Archbishop Aloysius Stepinac of Zagreb, he had been stranded in Chicago when Germany invaded Yugoslavia. A troubled priest, who had over one winter and one spring taught Marie-Jeanne and Richard the Rite of Christian Initiation, whom Berta foreswore Marie-Jeanne not to leave alone with Richard. ‘Colonel Belisle and I offer it for your service, Father.’

“We read in Sacred Scripture: Our true home is in heaven, and Jesus Christ whose return we long for will come from heaven to save us.”

Marie-Jeanne looked up to her husband, shoulders as wide as the horizon, garrison hat held before him, greatcoat belted at the waist. In her heart, he became her husband that October morning four decades earlier when in Spirit Falls Graded School a six-year-old lout in overalls and brogans assumed she was an ignorant Canuck and translated the teacher’s question into his gibberish Serbo-Croatian. That boy had grown into this husband. “Husband.’ The word formed against the gray-white sky in firm, precise and black gothic script firm. ‘Hers’ resounded in a major chord. The farmhouse, the village, the vast north woods had been their Eden until that day they were cast out. She shivered. Father Vukelich had not given them their first communion. The grievously flawed priest nodded to the undertaker, who touched a switch, the coffin began descending into the earth.

In sure and certain hope of the resurrection to eternal life through our Lord Jesus Christ, we commend to Almighty God our brother Lott, and we commit his body to the ground/its resting place: earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust.

Yet, she had brought Chrystelle, then her twins to him, to Eden, for baptism.

The Lord bless him and keep him, the Lord make his face to shine upon him and be gracious to him…

Was in a mere decade after that first day in first grade they became husband and wife, if not in the eyes of the law, at least before God’s averted eye? His dreams shattered, she found her Ricky on that Colorado mountain pasture. The sheep camp bunk was surely no wider than a 2X6 and surrounded by 6000 fretful sheep with two sheep dogs watching them intently. For birth control, she counted on her fingers the days between periods, said a little prayer to the virgin mother, and gave it her all. Nine months later Chrystelle arrived with the awful inevitability of God’s plan. She smiled––she must have one night forgotten to ask the Virgin’s intercession.

the Lord lift up his countenance upon him and give him peace.

A third word wriggled in the air and traversed the county highway to settle in the field of corn stubble… infidèle. Murielle, obstinate and articulate Sephardic Murielle, arm folded through her father’s other arm. Richard, inarticulate and uncomprehending, stood between them. Always, he stood between them.

“Now let us pray as Jesus taught us….”

The soft impact of heavy snow on snow undertoned the discordant murmur of a Catholic and Lutheran prayer spoken together. ‘Our Father who art in heaven, hallowed be your name, your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.

He was in Okinawa, awaiting orders

Give us today our daily bread.

…and sent the power-of-attorney and pay allotment for $60.00 a month, keeping $12.00 for himself.

And forgive us our transgressions,

She was eight-months pregnant when Kitty appeared at her door, Murielle in her arms. Her Hasidic stepfather had cast her out. Her biological father, Reform Jew, denied her paternity. Richard, the idiot beyond all telling, had given Kitty Marie-Jeanne’s address. Murielle was Richard’s child. What could she do? She took her into her one-room apartment. Kitty slept with Murielle in the single bed, Marie-Jeanne on the floor. God, she had been so angry. Had Marie Jeanne not been pregnant herself, Richard would have found himself and his stupid power-of-attorney married to Kitty.

…as we forgive those who transgress against us.

She had forgotten, ignored, pretended, but she had not forgiven, and she loved him beyond comprehension. She ditched her pride, made up with her mother, and Chrystelle was born in the Army hospital at West Point. Richard turned, looked into her eyes, questioning. “Ricky,” she said, her voice hoarse, “if anything…anything at all happens to Chrystelle, I’ll leave you, I swear.”

For thine is the power…for ever and ever, The wind pushed a tear across her cheek. Amen

She startled. The VFW honor guard fired a ragged volley into the air. One of the Lange twins, Kemper or Kurt, croaked out an inarticulate command. Rifle butts staccatoed against the frozen earth. Another shouted command. Another ragged volley. The other twin, Kurt or Kemper––Marie-Jeanne still could not tell them apart––glared. They no longer spoke, some argument over folding the flag, which would be settled when one buried the other.

#

Richard Belisle

Richard stood before the floor-to-ceiling second-floor window of the farmhouse north wall. The outdoor furnace belched thick white smoke, the wind snatching it at the stack and rolling the writhing spirits across the snow. The furnace fan engaged and cold air rose from the floor vent. In an hour or so, the farm house would warm.

Richard stood before the floor-to-ceiling second-floor window of the farmhouse north wall. The outdoor furnace belched thick white smoke, the wind snatching it at the stack and rolling the writhing spirits across the snow. The furnace fan engaged and cold air rose from the floor vent. In an hour or so, the farm house would warm.

The coffee maker sighed it final gust. He sniffed the air. Not bad for a thirty-year-old German Tchibo coffee beans. They had been long ago Christmas present which Marie-Jeanne had sent from Germany, and which his mother had stored in the closet beneath the stairs. Coffee grinders were rare in those days in the Northwoods. Odd. Marie-Jeanne normally knew these things. But she had been pregnant with the twins, and they had taken on Murielle. It had been a chaotic December.

He poured a cup. He had been so happy when he gathered his family at Frankfurt-Main airport. He had just made E-4, which meant the tour was accompanied, which meant a housing allowance, which meant he could house a wife and family without living in utter and abject poverty. He had plans. He’d taken his GED, would attend University of Maryland on post courses. With a two-year degree would be eligible for officer candidate’s school, and support Marie-Jeanne and the kids like a real man.

It had been hard. It would be better. It wasn’t. He turned from the window and lifted the cardboard box to the desktop. What Marie-Jeanne had put up with to have Richard Walter Belisle as her husband. She was not one to suffer in silence. He lifted the faux-leather folder onto the desk, unzipped it and laid the contents in one pile on the low rough-hewn table. He woke with Marie-Jeanne sitting on his chest, her knees pinning his arms to the duvet. “You were crying,” she said. “What were you dreaming?”

“Nothing. I was dreaming of nothing.”

She’d find him walking the streets of the German village, Murielle asleep in his arms. ‘I’ll not live with this…this brain-damage, this rage,’ she said, ‘like your father.’ His world went white. “Like my father,” she said. She held his head, her nightshirt wet with his tears and pulled the stories from him as if each word were a K-Bar blade thrust in his chest.

He looked down at the papers before and picked up the stapled pages, the farm mortgage. These four pages had loomed like a writ of excommunication over his childhood. Twenty-two dollars a month the bank required. The entire note, eighteen hundred dollars and change, was less that one-half month’s his current pay. He said the mortgage down and picked up the single sheet of paper, typed with strikethroughs, and saw the sweat-drenched Army clerk-typist stripped to the waist punching out the text with two fingers.

First Sergeant Lott (NMI) Belisle, ****Infantry, United States Army. For meritorious service in connection with military operations against the enemy on Okinawa, R.I., on 8 May 1945. Anti-Tank Company, *** Infantry, was bivouacked about one thousand yards south of Kakazu Ridge. An enemy artillery and mortar concentration fell suddenly in the air. One round scored a direct hit in a foxhole demolishing it and burying its four occupants. Sergeant BELISLE, with utter disregard forces own life, left his foxhole and worked his way through the fire to the buried men. His initiative and courage inspired others to follow him. Working feverishly, he helped throw the aside the dirt. The lives of two of the men were saved by the prompt efforts of Sergeant Belisle.

One had time to kill in the pre-Vietnam Army. Uncle Sam paid an E-2 $78.00 a month, didn’t lose much money telling you to show up for morning formation, then order you to get lost and stay out of trouble the rest of the day. Okinawa was not their final destination, which was, they were told, none of their business. His buddy, Bondarenko hired a taxi to tour the island. Rick remembered only the name Kakazu, but the taxi driver knew. He showed them markers––Hacksaw, Conical, other names. They looked up vertical ridge faces, which the G.Is climbed up using cargo nets. The young men walked across shell fragments a foot deep for hundreds of yards, came upon unseen Japanese tunnel entrances until you stepped into them. They wondered aloud how anyone survived on that battlefield, but survive they did. By the second day, young, innocent, envious, they had found their smart-ass voices, regretted missing the battle, the chance to fight, to become heroes. Fuck.

He now picked up a 5X7 black and white photo. The faces were slightly fuzzed, and he could not remember posing. He had his baseball mitt strapped into his belt, the white second-hand suit slung over his shoulder, and looking over the photographer’s left shoulder. Marie-Jeanne in a white dress with a bible and cross in handed had turned her head to him as if sensing disquietude. He raised his head at the sound. A Plymouth Voyager turned into the driveway. He knelt to the air vent and felt the hot air.

#

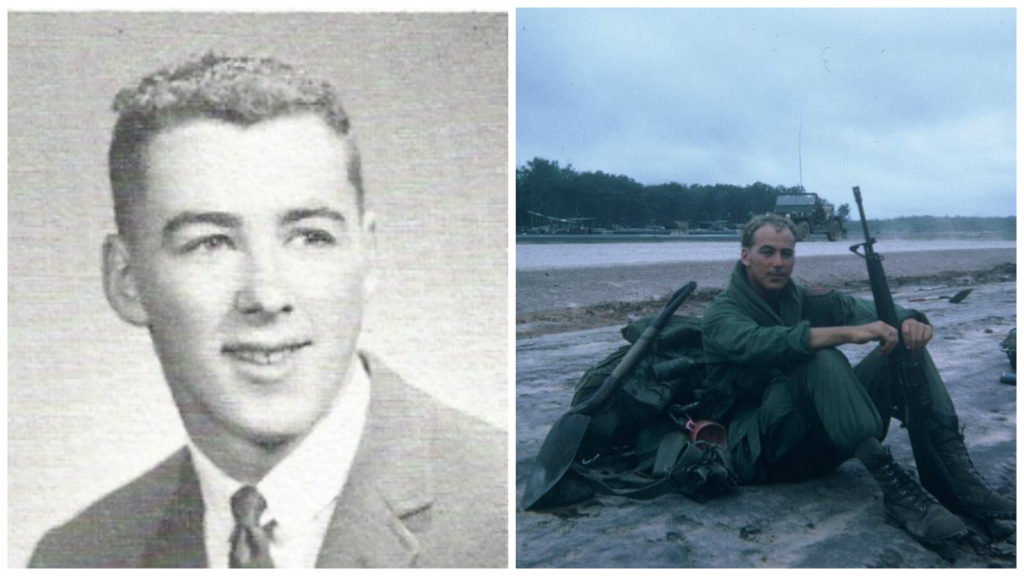

Murielle

Warm air rattled through the farmhouse heating vents. Rivulets of moisture tracked down the kitchen sink window through the inverted arc of frost. Murielle poured two cups of coffee, waved the schnapps bottle in her Uncle Zoran’s direction, and poured until he signaled the halt. “Grandma?” she said.

“Just coffee, my angel, and a little milk. No sugar, but you remember that, don’t you? You are such a good girl.”

“Not a girl anymore, grandma,” but she smiled. “Where’s the Dutch oven? ” Berta waved towards a corner cabinet, floor level, and Murielle dropped to her knees, thrust her head and upper body within, as soon pots and pans were clattering across the kitchen floor.

“Ach, takva strka!” Zoran said, throwing up his hands. With shaved head and white walrus mustache, he resembled his idea of a 19th Century Russian Cossack, which, Murielle supposed, appealed somehow to his streak of Serbian romantic nationalism.”Hurry with dinner, Lepa Ciganka. I’m famished.”

Lepa ciganka…pretty gypsy girl. Pretty gypsy girl was better than ‘stuck-up bitch.’ On the streets of New York black guys mistook her for a black girl and didn’t like it big time if she ignored them. Murielle indeed favored hoop earring, long skirts with metal clasps for rearranging the fall of material, multi-colored shirts with color-matched stockings over muscled calves and purple boots over battered dancer toes. Murielle Belisle, striking dancer and prosaic seamstress, the latter skill fundamental to a student dancer and choreographer. One had to construct ones own and the cast costumes. She watched the sister touch the brother’s gnarled hand and thought, ‘Grandmother, Grandma, what am I ever going to do without you?’ she thought, then… “Ach, Grandma! You aren’t going to smoke, are you?” Berta smiled and slid the cigarette pack forward to the table’s edge. Murielle clambered upright, tapped out two, and lit both.

Lepa ciganka…pretty gypsy girl. Pretty gypsy girl was better than ‘stuck-up bitch.’ On the streets of New York black guys mistook her for a black girl and didn’t like it big time if she ignored them. Murielle indeed favored hoop earring, long skirts with metal clasps for rearranging the fall of material, multi-colored shirts with color-matched stockings over muscled calves and purple boots over battered dancer toes. Murielle Belisle, striking dancer and prosaic seamstress, the latter skill fundamental to a student dancer and choreographer. One had to construct ones own and the cast costumes. She watched the sister touch the brother’s gnarled hand and thought, ‘Grandmother, Grandma, what am I ever going to do without you?’ she thought, then… “Ach, Grandma! You aren’t going to smoke, are you?” Berta smiled and slid the cigarette pack forward to the table’s edge. Murielle clambered upright, tapped out two, and lit both.

“Can we at least shut off your oxygen tank or do you intend to blow us all to hell?”

“Oh, I’ll be careful. I want to see a grandchild out of you girls one of these days.”

“Not this one, grandma. I got things to do.”

“You’ll always have time to do what you do, but you won’t have time to have children.”

Murielle adjusted Berta’s blanket, straightened the oxygen hose and patted her grandmother’s shoulder. “I can quit any time I want.” She’d cut the vegetables smaller, and instead of roast, she’d make a stew. She propped her left elbow on her hip holding the cigarette aloft, watching dusk descend over the south field. Here, she and her sister, barefoot and in bib overalls, gathered eggs and milked cows. Here, she and Berta gossiped over their morning smoke and cup of coffee about anyone unlucky enough to be not there. Here, she had been as happy as it was possible to be.

Uncle Zoran leaned forward, both hands crossed atop his cane, now speaking Serbo-Croatian. “If they don’t have a talk with the twins, you’ll get grandchildren soon enough. Apple doesn’t fall far from the tree.”

Berta raised her hand as if saying ‘God’s will.’ though she didn’t believe. “You haven’t changed your mind, you stupid ass, about returning to the old country?”

“Tito, the Croat bastard, is dead. Yugoslavia needs people who know business.”

“You’re a fool, Zoran. I knew when I first wiped your bare ass I knew you were a damned fool.”

“Who’s done damn well for himself, thank you.” He twisted in his chair to look out onto the darkened drive-way, where his polished and gleaming black Cadillac was parked. “Done well,” he repeated, nodding his head, agreeing with himself. “I want the twins to work construction in Chicago for me this summer. Talk to Richard. He listens to you.”

“Asshole that you are, it’ll be good for the boys. Won’t sit around the house playing those computer games.”

“Dobri radnici, those boys.” Berta looked up. ‘Good worker’ was an Academy Award level immigrant compliment.

“Too hard on the girls,” Berta said in English, then reverted to Serbo-Croatian. “Too easy on their twins. If Ricky and Marie-Jeanne had had six…eight children, they’d get it just right by the last one.”

As the old folks slipped into the old language, Murielle’s attention slid to getting dinner ready. She chopped carrots, potatoes, and celery first lengthwise then across and dropped them into the smoking lard. Olive oil was a forbidden fruit in the Upper Peninsula, but folks seemed to survive without it. Studying the food-stained cookbook, she looked up, the English sentence catching her attention. “Richard did the best he knew how, I think. Don’t you?” Berta shrugged. Children became pretty much their own people around their second birthday, but it was something each mother learned in their own time. “Grandma, remember when Chrissy and I put up all the hay that summer. We worked like coolies…must have been two-thousand bales and you gave us the same cookies and milk we had earned at eight-years-old gathering eggs.” She looked up.

“Do you remember Marina’s twins,” Berta murmured, her smile sly.

“Well, yes…” Murielle admitted. The neighbor boys, Marina Krikowicz’s twins––there had been some youthful drama between this Marina and Richard, Murielle had heard––would appear in mid-afternoon, shirts off, like young beagles loosed of their leashes. “Strapping lads. Loved to show off their muscles. Eh, you were the cunning one, weren’t you, Grandma, using pretty girls to attract free labor?”

She searched through the drawers, checking for a sharp knife. All were dull save the cleaver, which grandma used to gruesomely separated the chickens from their heads. Since grandpa had gotten sick, he neglected the knives. She paused, missing him, then picked up the heavy blade and made short work of the roast.

“Where are your spices, Grandma?” Twins? Murielle considered this confluence of thought. Marina had twins. Her father sired twins. Was it the father’s or mother’s line that predisposed to twins. And Marina looked at her dad with more than a neighborly interest, Murielle thought. She stubbed out the cigarette.

“The cabinet above the sink.” Berta paused, willing oxygen to replace the cigarette carbon monoxide in the few functioning lung alveoli. “….in the white box.”

“Ah,” Murielle said, pulled over a barn-board bench, and on tip-toe, pulled down the plastic case. She searched through the spice box for turmeric and chili powder but found an envelope of cumin. She’d use it all. Her brothers, picky little eaters, would eat anything if she overdosed with cumin. She could even sneak greens into meat loaf, providing she puried the greens––no kale larger than a micron or they’d pick out it like dogs picking around a bacon-wrapped deworming pill.

“Murielle, the dancer, Chrystelle, the engineer.” Uncle Zoran toasted her with his coffee and schnapps, holding it aloft. He wanted more. She fluttered her fingers–hold your horses––while perusing the food-stained recipe. The misogynist old bastard was right. Sometimes, you really couldn’t tell who people were by just looking. Zoran continued, “Murielle, the cook, Chrystelle, the baker; Murielle senses, Chrystelle measures; Murielle dances, Chrystelle builds.”

You had to watch out for those Serbian boys, always boys whether eight-years-old or eighty; handsome bastards, but still bastards. She refilled his drink. The vegetable blanched, she screened them out and dropped the 1/2 inch pieces of floured stew meat to brown.

“Make sure, darling, that you brown the meat on all sides.” Berta made as if to rise to supervise, but sat back. The effort was too much.

“Yes, Grandma, I remember. ” She found an envelope of buillion, opened the package. It was solid. She banged it with the tenderizer hammer, sprinkled it into boiling water, and when dissolved, poured it into the Dutch oven, How was it possible? When Berta scolded, she felt bathed in love. When Zelma, her New York grandmother, complimented, Murielle felt as if the old bitch were dripping acid into her ears.

“Marie-Jeanne’s been a good mother to you.”

“Step-mother,” Murielle corrected. “I am a step-daughter, which she makes clear enough.”

“We loved you all,” Berta said, touching her wrist.

“You love me, grandma.” Murielle corrected. “Grandpa did too.”

Zoran turned to the blackness beyond the window. “Ah, Ricky and M.J., they back.”

*

A Farmhouse

“Shall we turn here…go back?” Marie-Jeanne said.

“Shall we turn here…go back?” Marie-Jeanne said.

“We can,” Richard said. But they remained there, where the town road intersected with School House Trail. The late afternoon northwest wind carried moisture-laden dark clouds forewarning snow. A wispy and intermittent easterly breeze agitated the swamp grasses on the abandoned Scullen Farm field. Tamarack, tag alder and other brush had self-seeded about half-way across the hay field. But immediately before them, the tangle of lilac and crabapple trees and tiger lily beds grew wild around unnatural mounds, monuments to sweat, hard, hard work and heartache, a farmstead abandoned.

“It’s as if they had never existed.”

“They had been near enough the end of us,” he said.

“We were happy here, weren’t we?”

“I doubt we’ll forget them.”

“I will never leave you, Ricky.”

“I know. You realize that you are calling me ‘Ricky’?”

“Is that right? When did I change?”

“You mean from ‘Ricky’ to Richard? When I became a second lieutenant. You were awed by my presence and stature, the might I wielded in the world.”

“Bullshit.”

“That word seems inappropriate to your lips, you so cute, small and all. But you use ‘Ricky’ at the farm…from our past. You address me formally, ‘Richard’ and appropriately so, I might add, in the larger world ”

“Remind me to gouge your ribs really hard. Bring your head down to me level,” she ordered.

“Don’t pinch my face.” He said, but did as ordered. She kissed his cheek. “Ricky, you know I’ll never leave you.”

“Chrystelle is as safe in Saudi as she ever was in Washington, D.C.”

“That reassures me how?”

“Those girls were constant trouble. Remember the telephone rang waking us at 0230?” Richard had formed his left hand into a telephone and spoke into the small finger, voice emulating the sound of a heavy-set southern policeman. ‘Major Belisle, this be you? This is Springfield Police, Rolling Road station, glorious Commonwealth of Virginia. Sergeant Hughes speaking. Do you know where your daughter, Crystal, her name is, is?

“”Downstairs sleeping peacefully in her bed?’ I replied.”

“No, not there, ho ho ho. You get two more free guesses.’

She’s there by you?”

“That be true…very true.”

“in jail?”

“Why, Major Belisle, you give me faith in the strength of our armed forces, the intelligence of its officer corps. Improved some since I served. Yep, we have her locked up. Teen drinking party.”

“Can I leave her there till morning?”

“Ho ho ho, no sir, you need to come get her now.”

Marie-Jeanne laughed into the darkness, the road now bordered with the night dark spruce forests. “I made you get her. Those could get into and out of more trouble.” They turned around and began walking from whence they ca.. “If there was trouble, Murielle always seemed to be somewhere in the vicinity.”

“I found her sitting on the doorstep, weeping.”

“Because the police broke up her beer party. She was always the impresario.”

“Those two do love one another.”

“Ricky, I am so afraid for Chrystelle.”

“We’ve survived some close calls ourselves, haven’t we, and we’re none the worse for wear.”

“Ricky, this reassures me?”

“Chrystelle is in air defense. She shoots planes down. She’s the badass.”

“I’d really like it if you stop talking.”

They walked on in silence toward the farmhouse lights. Richard spoke. “M.J., I am tired. The Pentagon…the commuting…I don’t think I can do it anymore.”

Marie Jeanne didn’t reply until they crossed the white pines in the Belisle farm yard. “What do you have in mind?” she said.

#

Danton Larionov

“To the Great October,” Roman Baranov toasted.

“To the Great October,” Danton Larionov replied. They touched glasses and knocked back their vodkas. Danton, square-shouldered, Slavic-short and stocky, hair combed straight back, caught his reflection in the mirror. He was handsome. The left side of his face was handsome. He did not turn full-frontal for the right side was grossly disfigured. An infected wound had healed poorly, giving that side a skull-like appearance, like Koschei the Deathless. Passers-by glanced away. Ah, an Afghanistan veteran, they would think, an afghantsev. No. It had been another war. “Perestroika and glasnost have been good for you,” he said.

They sat at the Sword and Shield, the KGB watering hole on Lubyanka Square. The tavern had changed little save for portraits of KGB chairmen, which were mounted or removed with the political winds, since his first visit forty years earlier. Danton transferred a piroshki, a piece of cheese and pickled vegetables from the serving plate to his own. Roman refilled their shot glasses from a frosted bottle.

“Indeed, Danton, indeed.” Roman dressed like a Westerner, of which more were appearing every day in the Soviet Union. He wore a suit of English-cut, a heavy wrist watch, and good shoes, all as yet unobtainable in the Soviet Union. Perhaps, the passers-by might think, he was the son or grandson of an emigre become wealthy in the west returning to explore business opportunities. On second glance, it was clear he was Russian––his carriage, a lifetime of cigarettes, vodka and pickled foods, the very impress of the Russian language on the physiognomy. Baranov’s wife was English, though of an Russian emigre family. It was reported there was property in London. There was a certain kind of Russian whom, when the shit got thick, got thin, they emigrated. Stalin understood them, and shot them. But that was then; now was now. The ersatz Englishman opened a pack of Benson & Hedges, offering one to his friend, lighting both with a gold butane lighter. “And how is it by you, materially.”

“I eat.” Danton, said. “Two-bedroom apartment…176 square meters. More space than I need since Lyudmila left me.”

“Fickle, these women. You are good to be rid of her. She had grown fat.” Roman bit on a large pickle. “On kanal 2 last night, they showed American gun camera footage in Iraq blowing rag heads to hell and back. However, the video of stealth bombers attacking SCUD missiles interested me . Think any of your Maskirovka training stuck with’m?” In the early-1980s, Danton had taught deception techniques in Iraq to divert UN weapons inspection teams.

Danton shrugged. “I saw the newsreel. The bomber was blowing mock-ups to smithereens.”

“You can tell the difference?”

“Empty wooden tubes explode differently than fuel-laden metal canisters. I assume that American general with the German name is just passing disinformation…deceiving the foolish.”

Roman saluted Danton with his glass, but sipped. The drinking competitions of young men were decades in the past. “I understand you are eligible for retirement.”

“They’ll carry me out of there feet-first. Who can live on that pension pittance?” The Soviet State had raised military and civilian retirement stipends to encourage old generals to retire, but hidden inflation had eaten it up. In the USSR retirement meant poverty.

“Have you considered sources of supplemental income?”

“What? Spy for the British?”

“Danton, let’s be honest with one another. I myself doubt whether the USSR will celebrate another Great October. The Berlin wall has been torn down. When scar-faced Gorbachev refused to shoot the counter-revolutionaries, well…the USSR is next.” Through the mirror Danton scanned the room with the undamaged side of his face. Such chatter ten years ago got you five-years; In the old days, it got you executed. “By the way, I’ve run into your Ekaterina Soroka recently. She’s doing alright for herself.”

Danton crushed his cigarette in the ashtray. “Why is this important?”

“You had a thing for her if I remember correctly.”

“Old times. We were kids in the village…Suzdal.”

“When Brezhnev was selling Yids to Kissinger…mid-70s…Professor Soroka…what was his relationship to her…father, uncle or what? In any case, our professor in the deception course…his influence tanked when Khrushchev retired…managed to obtain her a posting to East Berlin when you were with the Soviet Military Mission in Frankfurt. Had you ever run into her there?”

Danton didn’t reply, but rather, asked, “What is she up to now?”

“She writes fables with a political slant for Novy Mir. She just got some kind of stipend…Fulbright, maybe…to study Slavic folklore in the Balkans.”

“I’ve not seen her by-line,” Danton took another of Roman’s cigarettes.

“She writes under a pseudonym…some French name…Charbonneau, I think.” Danton nodded. He had perhaps read a few of the stories. “But how’s your German? Still pretty good.”

“They know I’m Russian when I speak.”

“We’re visualizing setting up a little company in Dresden, then if it becomes profitable, establish subsidiaries in Munich or Stuttgart.”

“Lot of rubles you’re talking about.” Danton had run operations in West Germany. Soviet-funded moles cost a lot. The East Germans were better at it…used lovelorn secretaries. But the Stasi now worked for the BND.

Roman spread his hands. “You have to spend money to make money…for the motherland,” he added quickly. “I won’t bullshit you, Danton. You know how to do this shit.”

“What is the mission?” Danton asked.

In turn, Roman sidestepped Danton’s question. “The company provides generous recompense…pay expenses…apartment, car, travel…plus $500.00 a month…hard currency.” Sophisticated KGB operative and man of the world, Roman became the pre-revolutionary peasant buying a cow, slapping a handful Imperial rubles against his palm to encourage movement in the negotiations.

Danton rubbed his face, smooth to scarred. $500 hard currency exchanged for black market rubles was more than a KGB colonel’s annual salary. “Remember when we arrived back in Moscow after the Cuba mission?”

The TU-154 had returned the GRU team to Moscow Vnukovo. KGB buses awaited. They were driven into the Lubyanka, dismounted, taken to the basement, to the crematorium. They saw the naked man strapped to a pallet before the furnace door. ‘A lesson to you mother fuckers,” their ‘guide’ said. He survived two hours, slid feet-first into and out of the furnace. The GRU colonel had spied for the British, exposing the movement of missiles and nuclear weapons to Western intelligence. “It’s a whole new world, my friend,” he said.

“Not so new,” Danton answered.

“Well?”

“What is the mission?” Danton repeated.

“There been a lot of money hidden in Soviet mattresses over the years. There’s a market for Western automobiles.”

Danton finished his drink, thinking. This sort of thing he had done before.

*

Ekaterina Soroka

Ekaterina Soroka could barely close her mouth from the happiness suffusing her body. Paris this late October 1990 was extraordinarily beautiful. The morning sky was cloudless, the air crisp but warming. The late morning traffic traversing the intersection of Boulevard du Montparnasse and Avenue de l’Observatoire was subdued. An intermittent breeze, fresh and clean, as if filtered through the trees and pathways of the Luxembourg Garden, rustled the potted bamboo hedge of La Closerie des Lilas. She raised her sunglasses atop her new short, Parisian cut, rummaged without looking in her new shoulder bag for her lipstick, paused, then lowered her sunglasses to hide her eyes, and looked around. Would a Parisian woman openly check her appearance? The metro had been full, the walk through the Luxembourg garden breezy; certainly, her hair was in disarray. Should she ask ‘Les Toilettes, ou sont elles?’ Marie-Jeanne would have known Parisian customs, but Ekaterina was Russian. This was her first trip outside of the Soviet bloc, the Council of Soviet still debating the bill on Freedom of Movement. Soviet people were country bumpkins, ignorant of civilization.

“Madame?”

Her heart stopped. Parisian waiters, she had been warned, could be extraordinarily difficult if your French was not parfait. Would he notice a hint of Slavic accent and pretend not to understand?

“A simple espresso with…” She fluttered her fingers simulating slight embarrassment at the hour, “with perhaps a small brandy on the side. Would there be something light that you’d recommend to munch on while I organize my morning and wait for a friend?” She fluttered her eyelashes. The sentence in French had passed her lips her choking.

The waiter paused, put hand to chin as if giving serious consideration to her request, then spoke rapidly, his hands signaling options and choices. She looked up through the cafe’s glass ceiling, pursed her lips to simulate what she thought was the thoughtful French look, and repeated the one item she recognized. He nodded, his expression indicating the choice was eminently wise, and left, returning almost instantly with the espresso and brandy. “You can be patient?” he said. “The boss is negotiating with the cook about the menu.”

“He can take all morning. My friend…she makes promises, but…” Ekaterina gave her best feminine simulation of a Gallic shrug. She had no idea when this dear but unreliable friend might appear. Each acknowledged that people, save the two exceptions standing within the one-meter circle, were difficult to manage. He inclined his head and departed.

Ekaterina saw she was gripping the tube of lipstick. She touched a button and released the small, unobtrusive mirror engineered onto the tube. What these Westerner wouldn’t think of next!

Ekaterina sipped her brandy before the espresso to settle her heart and looked around. Here, in the Fall 1934, in this very place, perhaps this very seat, her seventeen-year-old mother had her affair with Diaghilev. There were certain women…her mother, her grandmother, herself…destined to have other women’s men break their hearts. She felt her heart speed slightly and closed her eyes. She had made love with him in Dresden, but in Berlin with the trap ready to snap she warned him off. With her eyes, she warned him off. How desperately she had wanted his child. And she would never see him again.

<<<<>>>>