Bihac, Bosnia-Herzogovina

WWII Massacres, Bosnia

Last week Patrice and I went to Bihac, Bosnia-Herzegovina for our ninth wedding anniversary. Driving from Bihac to Velika Kladusia (border town between Croatia and Bosnia-Herzegovina) one encounters roadside memorials commemorating WWII tit-for-tat mass executions, chetniks and partisans, this village massacred in reprisal for that massacre, the memorials erected during the Communist era, thus those massacred by partisans as yet unacknowledged.

Bosnia was part of the Ottoman Empire until 1890 when Austro-Hungary annexed the whole of Bosnia, and where, twenty-odd years later, down the road in Sarajevo, Gavrilo Princip assassinated Archduke Ferdinand and his wife, Sophia bringing on a very Long War. Some suggest that the long war Princip initiated in Sarajevo in 1914 ended in Sarajevo on 29 February 1996.

Bihac has reminders of the April 1992 to February 1996 Serbian siege. Concrete walls show shrapnel and bullet gouges. There remain a few burnt out public building (hotel? Government center?). The River Una shoreline is a long park with biergartens with a sense of long-ago Austrian Gemutlichkeit.

Pulses of Yugoslav refugees have populated America. In Boulder, Colorado, we sold our car to Bosnians, the Muslim Bosnian husband in a Serbian concentration camp from 1992-94 (treated well, he asserts) while his wife and two children lived in a refugee camp in Ljubiana. In 1947, my Gleason (WI) farm woman neighbor, Maria, still does not know that she missed execution by probably days as the British Army forcibly repatriated Slovenian refugees back into Tito’s hands. My grandparents emigrated in anticipation of conscription for the Balkan Wars, leaving a small Slovenian town north of Ljubljana in 1905, for the steel mills of Joliet, Illinois. Pre-WWII, cousins would write my mother, importuning her to send nylon stockings, money, etc., the Americans being so rich, the Slovenians so poor. My mother, a crusty customer, refused; we were poor enough ourselves. The letters stopped in 1941, never to be continued. My sister visited Slovenia and searched for the village. It seems no longer to exist, the inhabitants massacred some night sometime between 1942-1947 by either Germans, Chetniks or Partizans.

We continue to explore in the vicinity of Rovinj, Croatia. The Adriatic fishing village, three hours from Zagreb and six hours from Venice (by train plus bus; less by ferry) is a long way from most anywhere, but then, so is Gleason, Wisconsin, three hours from Madison, WI and six hours from Chicago’s O’Hare Airport. Rovinj, Croatia and Gleason, Wisconsin are both pretty quiet places in the off-season.

Monkodonja, Istria, Croatia

About seven kilometers SW of Rovinj on the back road to Pula is one of those Bronze age hillforts, Monkodonja (pottery shards indicated it conducted trade with Mycaenaean Greece). Excavations suggest the city ended violently, though when it existed, the citizen’s hilltop view of the Adriatic was wonderful. There are 321 hilltop (discovered so far) pre-historical fortifications, many of which give evidence of violent end.

I had mentioned earlier that the Istria Peninsula has long been inhabited and the evidence is fortifications, many unsuccessfully defended. There is no written Neolithic (i.e. New Stone Age) nor Bronze (think Stone>Brone>Iron) age history (the Greek Bronze Age is preserved in oral Homeric epics) hereabouts, though Rovinj not all that far (about 800 miles by sea) from Greece. Carbon-dated bones date the destruction of the Monkodonja fort (occupied between 2000 and 1200 BC) when regional drought sent peoples maurauding (think Exodus, or better, Genesis, chapters 37-45, Joseph saving the people of Israel from starvation).

The history of the region is thus: this tribe plunders the better provisioned neighbor, then occupies the land peaceably enough until the next hungry tribe appears on the doorstep (go here if historic climate change interests you) .

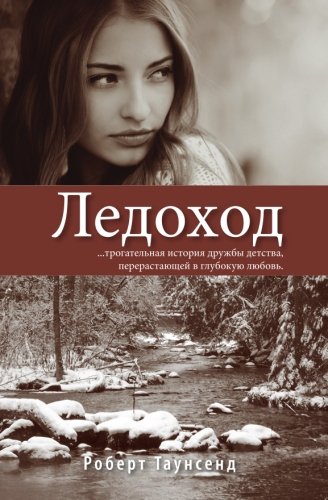

So what’s all this Sturm und Drang have to do with a gentle little blog post? Is this what you all signed up for? I am not sure. Well, it’s about what I write fiction.

‘The Executioner Son’ emerges from my marble block head, chip by shaving by sand-paper grain. Richard Belisle observes Danton Larionov closely. The range is 550 yards with slight elevation, the wind right-to-left intermittent at about 5MPH, with drizzle. Ricky, using a shop-modified M-1 rifle, .30-06 Winchester cartridge, 200 gram soft-tip bullet (186 grain powder load), shoots. The shot is true, but Danton’s surveyor’s transit deflects the bullet.

Thus begins Danton’s story.

Somehow, Yugoslavia’s bloody history speaks to Danton’s history of peoples living upon the borders where extermination is distant memory and imminent possibility.

In a room in the Hotel Emporium, Bihac, Bosnia-Herzogovina, twenty years ago a city besieged.