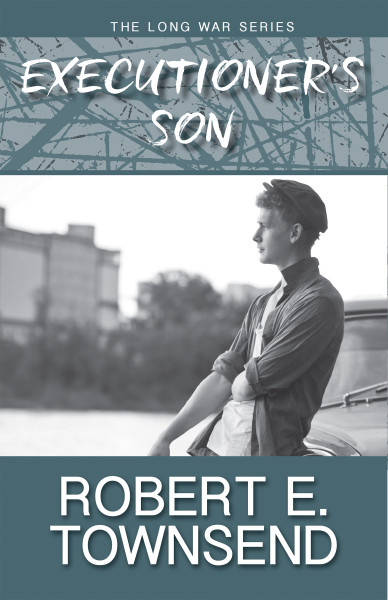

Serge Kotlar and I (Yay!, Merrill, Wisconsin) translated Thirteen Coats from Russian to English as research for the next book in The Long War series, The Executioner’s Son. I read and speak Russian and have studied the country and its culture since my 17th year on earth. Although my academic background introduced me to the catastrophe that was Russia’s twentieth century, I am only now hearing the personal stories. I had observed Russia and Russians as though through reversed binoculars.

Evgenii Belodubrovskij’s Thirteen Coats is a meditation on Leningrad, now Petersburg, Russia, from his birth in 1940 on the eve of the German invasion and three-year blockade to the present. Russia’s twentieth century traumas––two world wars and a civil war which, truth be told, endured for decades––the collectivization of agriculture, the Great Terror, the slave labor camps, the Gulags. When Stalin died in 1953, they held ten million souls.

How can one comprehend its enormity? If there is a big picture, perhaps it is within the pages of The Black Book of Communism in which French humanists enumerated the tens of millions murdered in the name of communism.

Siege of Leningrad

Numbers boggle. They empty tragedy of content. Stalin, the cynic, said that one death is a tragedy; ten-thousand deaths a statistic. The Russian Memorial is a society dedicated to telling the story of Russian vast tragedy one-by-one. (Orlando Figes, whatever his academic malfeasances, has opened the Russian stories to the West). see [http://www.orlandofiges.com/familyHistory.php]

I am a Vietnam vet, 65 years old. My longevity tables suggests I can expect to live 93 years. Self-medicating his trauma with alcohol, drugs and tobacco, the Russian male of my cohort has now been dead ten years, his statistical lifespan 53 years. But Russia’s trauma has yet run its course.

At Michael’s on Monroe St., Madison, WI

Evgenii is a friend whose wise counsel on the Russian soul illuminates. However, I would be his friend whether his counsel be wise or not.

An anecdote. It is late summer 2010. He with his wife are visiting their daughter, a graduate student at the UW Madison. We meet for ice cream at Michael’s Frozen Custard on Monroe Street. His wife and three daughters––all beauties and all terribly quick-witted––join him. They listen to us yak. He cascades Petersburg-accented Russian upon his listeners like Dostoevskij’s Marmeladov (in Crime and Punishment). When he pronounces, as fathers are wont to do, they roll their eyes. Faaather! They so reminded me of my own three daughters, when I pronounce. We reassure one another that we are not blithering, though beloved idiots as our skeptical daughters loudly assert with the silent roll of the eye.

Though Evgenii and I have much in common, we came to manhood in worlds apart. Not only does he interpret the world through another language, he came of age in in a universe far far away.

The Petersburg Russian Evgenii Belodubrovksii speaks is difficult to translate. Sergei Kotlar, who translates my novel into Russian, did the monumentally difficult first draft, after which I worked to balance Russian melody with American meaning. Evgenii’s meaning is more poetic than factual, the key to which may reside in this footnote appearing late in the book:

…Once, in a small 1916 Petrograd magazine, I came across a note – a review of the thin leaflet by Tsiolkovsky “In Defense of the Aeronaut.” There was a lot of mumbo-jumbo about imagination and the author and outer space and other provincial meanderings, but the ending line was brilliant––“He wanders round about the truth!”

So there it is, my friends. You can laugh, or not, but it describes us wanderers, the truth-prospectors.