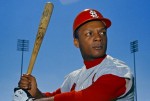

Cardinals Curt Flood 1968

I’ve spent a great deal of time composing this blog because I am writing a scene, time frame 1961, in which two young men, Rick Belisle and Andrei Byelenko, minor league baseball hopefuls and sons of Slavic immigrants, are discussing in context of their careers the baseball reserve clause, the US Selective Service[1] system, Russian serfdom and the Alabama penal system. I am also reading a selection of current book publishing contracts and note the commonality between serfdom and a routine publishing contract.

I write fiction and I publish the fiction I write–Two tasks requiring two states of mind that share commonality only in their complexity. Why bother both writing your fiction and marketing it, you ask? Find an agent, who finds a publisher, who markets your fiction. Each does what s/he does best.

Nope. If it ever worked that way, it don’t no more.

When in 2005 or thereabouts I had finished two of five planned interlinked novels, I sought representation to a traditional publisher. It was as if I had returned to the 1970-75 American Army. Decisions were made distantly, somewhere along a convoluted and sclerotic chain of command.

I write literary fiction about violent men of action who seek truth with human connection. I compose narrative in the morning, marketing plans in the afternoon (day job) and my fiction marketing plans in the evening. I have been trained. For one-third of my military career I broke Soviet war plans, the next third wrote US war plans, and the remaining third puzzled over Soviet deception (Маскировка и дезинформация).

My blog readers are not writers, but intelligence (sub-specialties; counterintelligence, deception and counter-deception) professionals. (Now, if ever there were a distinction without a difference, voila.) If I am lucky my book readers will become the ordinary American soldier.[2]

Russian Serfs circa 1861

However, upon further reflection I realized that the relationship of the American writer to the American publisher was not as was the American officer to the American draftee circa 1960, but more like the Russian aristocrat to his serf circa 1859. Hold your guffaw and read on; you’ll be well served and less embarrassed.

Serfdom was abolished in Russia not out of Christian love but military necessity. Imperial Russia had been defeated in Crimean War. Russian Minister of War Count Dmitrii Miliutin recognized that slaves did not manage modern military equipment well. To create an army capable of fighting on the 19th century battlefield Russia abolished serfdom. The soldier serf did not command the independence of mind necessary to manage new military technology––the rifled gun had replaced the bayonet. When the Bolsheviks reinstituted serfdom, the Soviet soldier was massacred en masse until the German Army ran out of ammunition.

I served in South East Asia 1970-71, then Berlin, Germany, 1971-75. My army [3] was an ill-disciplined mob without a snowball’s chance of defeating our main enemy––The Group of Soviet Forces Germany––on the main battlefield, the North German Plain, without going nuclear. The draftees, weapons and command and control we Vietnam vets deployed to implement CINCUSEUR (CINCUSAFE) Oplan 4102 (conventional war Europe) were toast, were we to go to war against the Soviet serf army.

In 1973 the U.S. ended conscription. By 1978 when I returned to Germany as a war planner, the Army has restored troop discipline. The men were sharp and shaven––free men and volunteers. The US military had become a calling. We were still toast, but it was a start. Our command task now was to provide these free (wo)men [4] great weapons with durable command and control for war against the Soviet slave (or serf––there is a distinction, but probably without a difference) army.

I had nothing to do with deploying advanced weaponry.

I was however deeply involved in deploying the Command, Control, Communications and Intelligence systems (C3I).[5] We dreamed the dreams, wrote the requirements and found the money for, among many technologies, what we called ‘packet switched networks, i.e., the ARPANET, which led to the development of protocols for internetworking, where multiple separate networks could be joined together into a network of networks, i.e, the internet. Packet switching, for a host of reasons, gave us war planners confidence our C3I would endure the concerted Soviet attack, a confidence, we were to discover post-collapse of the Soviet Union, particularly the Soviet General Staff, shared.

In August, 1990, my oldest daughter, then an Air Force 2nd Lieutenant pathfinder, deployed forward of the 82nd Airborne Division into Northern Saudi Arabia for Operation Desert Storm (17 January 1991 – 28 February 1991). Great men deployed great weapons under great leadership to devastate Hussein’s Iraqi Army. That my second lieutenant survived and thrived was not foreordained; The NVA was also a third world army, and without oil money.

Okay, enough. Pick the laurels out of your ass; That was then; Now’s now.

This is the background to that which I encountered decades later when seeking publication––a long and sclerotic chain of command using primitive technologies we soldiers shit-canned decades before to encounter publishing contracts which, without great liberty in translation, resembled the medieval Russian laws and contracts[6] institutionalizing serfdom.

How could one otherwise interpret this standard boilerplate in a current publishing contract?

Author grants and assigns to Publisher the sole and exclusive rights to the Material throughout the Territory during the entire term of the copyright and any renewals and extensions thereof.

As Jake Konrath, one of three great American commentators the current state of traditional publishing notes, In other words, this contract is for the life of the author…, ( I’ve written elsewhere about slavery vs. serfdom in current American publishing contracts, so if that interests you, go Here.)

Change a few nouns and this contract language is 14th century Russian, not 21st century American. This contract language is for the life of the author, plus 70 years after his/her death, plus renewals and extensions. Who would sign this but an illiterate and desperate Russian peasant?

America’s intellectuals sign these contracts[7]. Go figure.

It was 40 years ago that baseball players broke similar contract language ( baseball’s reserve clause ) obligating[8] them to play for a single team until death.

Thus do I self-publish. Serfdom vs. slavery, in either case, a distinction odious to make.

[1] The US Army had inter-division sports teams and used the Selective Service system to find hot young prospects for their teams.

[2] Been in the military too long not to recall the great many shitheads among my men, peers and commanders. I don’t write romances.

[3] When I say ‘my army’, I am thinking collectively, i.e. US Army and Marines and the tactical Air Force and exclude US Navy and the Strategic Air Command. They were fighting a different war.

[4] There is another story here. The end of the draft brought women into the military in large numbers. We Neanderthal officers and senior NCOs had to figure out what to do with them. Their peers, the young men manning the next position, married them.

[5] C3I (Command, Control, Communications and Intelligence) systems provide integrated real-time support to decision-makers on and off the battlefield, transforming raw data into actionable intelligence. C3I encompasses strategic and tactical systems covering ground, sea, air and space operations – all built on advanced network architecture and global combat experience.

[6] This standard publisher’s contract clause could without much loss be translated direction from Соборное Уложение 1649 года (http://hist.msu.ru/ER/Etext/1649.htm)

[7] My favorite serf’s defense of serfdom is Scott Turow in a Salon.com interview.

[8] Curt Flood’s unsuccessful challenged the reserve clause and got the ball rolling toward free agency. Funded by his fellow players, Flood sued Major League Baseball privately. Flood eventually lost his case in the U.S. Supreme Court, but the battle educated countless players and millions of Americans about the fundamental inequity of the reserve system, which perpetually renewed a player’s contract, essentially binding the player to one club for life, or until that club decided to get rid of the player.